Gaming Protocol Paper

Tashi Protocol: A viable consensus engine for multiplayer games

Bobby Bhatia, Ken Anderson, Steve Marshall, Sean Tedrow, Austin Bonander

October 12, 2023

ABSTRACT

Distributed ledger technology has demonstrated a feasible future where parties may interact, transact, and own assets in a censor-resistant and decentralized manner. Bitcoin disintermediated financial transactions between transacting parties. Ethereum added decentralized compute to the equation, allowing parties to add logic to their transactions via smart contracts. Hedera Hashgraph emerged to offer fair ordering, fair access, and fair timestamps at a speed unparalleled by other public ledgers.

We propose a protocol in which a set of peers broadcast messages and agree upon the order in which the messages are to be acted upon at a high throughput and low latency sufficient to satisfy the performance requirements of the game industry.

Tashi Protocol enables multiplayer gaming sessions that don’t rely on authoritative dedicated servers. Instead, each player’s game client also acts as a local server, synchronizing with all other players in the game session through a consensus mechanism; reducing network traffic for the game publisher’s servers, providing fair ordering of game input messages, and guarding against certain classifications of cheats. Most importantly, the Tashi Protocol operates with high throughput and low latency necessary to support most multiplayer game types.

KEYWORDS

Byzantine, Byzantine Agreement, Byzantine Fault Tolerance, DAG, Consensus, Gaming, Multiplayer Gaming, Leaderless

1 INTRODUCTION

Web 1.0, or “The Static Web”, began in the 1990s and continued through the early 2000s and represents the early days of the public internet, characterized by static websites and limited interactivity. Websites were primarily informational providing users a read-only interface with limited ability to contribute or interact. During this phase of the web, the financial model revolved around e-commerce and banner advertisements. Websites earned money by selling products and/or services or leasing their website “real estate” to advertisers.

Web 2.0, or “The Social Web”, took place in the mid-2000s through the early 2010s and shifted toward more dynamic, interactive, and collaborative online experiences [1]. Users could contribute content, comments, and media. Social platforms like MySpace, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube emerged. The emphasis was on user engagement. In fact, the financial model of the web shifted toward a greater emphasis on user engagement, social interactions, and advertising. New revenue models emerged like the “freemium” model that offered basic features for free and premium features for a fee. Shared advertising and sponsorship models paid user creators for providing content that engaged the website’s user base. Virtual goods and micropayments became available. It can be argued that Web 2.0 added value to Web 1.0 with new features and new business models, improving access to content, convenience of use, and network effects. It can also be argued that, because web-based businesses got creative about advertising revenue models, the user became the product. This introduced a risk to personal privacy [2].

Web 3.0, or “The Decentralized Web”, began in earnest in 2008 with the launch of Bitcoin and continues today. The emphasis is on the democratization of the web, sovereignty of personal data, and privacy. Bitcoin demonstrated that individuals could financially interact without an intermediary, like a bank or payment processor. This model of the web emphasizes individual control of information, democratized governance, censor-resistance, and trust-free economies [3].

1.1 Innovation

With the emergence of Web 3.0 came innovation in building trustless and fair environments for web users to interact. These innovations included things like modern consensus protocols to support distributed ledgers that would eventually ensure a consistent state between a network of participant peers. These consensus protocols have been used to generate verifiable data structures. The most common data structure in the distributed ledger space is a blockchain. A blockchain is a distributed ledger where each block contains a set of transactions and a cryptographic reference to the previous block. Blocks, being linked to each other through this cryptographic reference, formed a chain of blocks where any observer can evaluate the chain and confirm that no historical blocks were changed or omitted. The trick with blockchains is how a new block is proposed and selected for inclusion.

The first major blockchain use case to be realized was Bitcoin, which is a Proof of Work blockchain. Participants in the Bitcoin blockchain network, also known as “miners”, would compete to solve a mathematical problem that would adjust in complexity depending on how long it took for miners to solve the problem. The winner of the solution published a proof of the solution along with the next block of transactions. The objective of this protocol, known as Nakamoto Consensus [4], was to pseudo-randomly select a leader from amongst a large group of miners and award that leader the right to draw transactions from a shared pool of proposed transactions and generate a block of those transactions with a cryptographic reference to the most recent successful block. The winner would receive a block reward for successfully generating the next valid block, as verified by future blocks that referenced the winner’s block. Proof of Work was a way to: a) slow down consensus such that too many leaders weren’t selected at the same time and minimize forked chains, and b) ensure that large numbers of miners could participate, preventing attackers from predicting and attacking the next leader. Bitcoin is considered one of the most secure blockchains because of the number of miners participating in the network and the value of the coin being high enough that effectively compromising the network is cost prohibitive.

The next major innovation in Web 3.0 technology was the Ethereum blockchain [5]. Ethereum was designed to be a general purpose, distributed computing platform, where developers could encode logic “on-chain”, enabling more complex use cases to be developed. This logic was encapsulated in a built-in Turing-complete programming language that allowed developers to build and deploy applications to the miner’s computers to be executed and recorded to the blockchain. These applications are called “smart contracts”. Ethereum originally used a Proof of Work consensus mechanism, similar to Bitcoin, to secure the network and produce new blocks to record the results of simple transfer transactions or smart contract transactions. It is now moving to a Proof of Stake consensus model.

This new model, implemented in what is known as Ethereum 2.0 [6], allows miners to stake their Ether, which is the network coin of Ethereum that holds value as the utility resource of the Ethereum network. Those who stake their Ether to participate in Proof of Stake consensus are called validators. Validators participate in proposing and validating new blocks, receiving rewards for successful validations and being penalized for malicious actions through “slashing”, or removing some amount of the staked Ether. The combination of pseudo-random validator selection, rewards, and penalties, Proof of Stake promises to be significantly more cost effective and performant than Proof of Work alternatives.

Hedera Hashgraph was the next evolution in public ledger technology with the addition of asynchronous byzantine fault tolerance (ABFT) with fast, fair, and final ordering of transactions. Hashgraph differentiated itself from other blockchain technologies in that consensus was leaderless and required ⅔ of its mainnet nodes to participate to even calculate consensus. It also introduced the concept of fair ordering, where no single node could manipulate the order of transactions. Compared to other blockchains that focused on how to obfuscate the selection of the next leader (miner), hashgraph focused on making a leaderless voting algorithm viable for distributed ledgers. Today Hedera Hashgraph is processing more transactions per second than any other public network and is amongst the most energy and cost efficient protocols in the public ledger space.

With each evolution of distributed ledger technology, more efficient and secure mechanisms emerged. Despite this progress, many use cases still require more performance and greater efficiency. Tashi is focused on solving this using the game development industry as a forcing function; combining best-in-class Web 3.0 technologies with Tashi’s optimized consensus engine to prove the viability of Web 3.0 technologies to a Web 2.0 audience.

1.2 Gaming in Web 3.0

Web 3.0 promised a new paradigm for gaming: self-sovereign in-game assets, fair and auditable game logic, privacy protection, and trustworthy incentive economies for stakeholders to name a few. In 2014 Huntercoin, the first blockchain game, was released. Huntercoin was an early exploration into the feasibility of Web 3.0 gaming, but struggled with bot intrusion and lag-related issues.

With the deployment of Ethereum in 2017, and its ability to encode logic into smart contracts, more complicated “on-chain” games emerged, including, arguably the most influential Web 3.0 game, CryptoKitties. Players could buy on-chain tokens that represented digital cats with a set of properties and functions that allowed trading and breeding to generate new and unique digital cat tokens. While promising, the popularity of CryptoKitties led to increased prices and latency on Ethereum across the board [11].

Certain games focus on player economics, building incentives into the game including models like “play-to-earn”. This model rewarded players with cryptocurrencies, including fungible and non-fungible tokens (NFT). Due to the speculative nature of cryptocurrencies, the play-to-earn model struggles to gain mainstream adoption. Many Web 2.0 game studios reject the model entirely as a type of ponzi scheme.

Today most Web 3.0 games focus on three primary value propositions: play-to-earn, self-sovereign digital asset ownership, and game finance (GameFi).

1.3 The Problem

Web 2.0 game developers are rightfully skeptical of Web 3.0 technologies. There are challenges to adoption, both real and perceived.

The real problems include:

Latency. Web 3.0 latency is measured in terms of a few seconds to hours, depending on the underlying protocol. Even a few seconds can be prohibitive for most gaming use cases. This is one reason why most use cases focus on asynchronous transactions that don’t impact the game experience itself.

Throughput. The most performant layer 1 and layer 2 blockchains are operating at around 5,000 transactions per second (TPS). Hedera operates at approximately 10,000 TPS. This throughput is shared between all projects built on these public ledgers. In-game events can require anywhere from 60-2,000 TPS depending on the number of players, game architecture, and synchronization model. A few games could exhaust the throughput of any single ledger, even if the latency problem was resolved.

Cost. Web 3.0 networks depend on balancing utilities with economics, ensuring that all peers in the network are fairly compensated for their contributions to calculating consensus. Some of these costs are directly related to the utility cost, but much of it is speculative and, in some cases, used as a mechanism to disincentive over-utilization of the network. For example, as CryptoKitties got more popular, more players submitted transactions to Ethereum, and Ethereum’s auction-model for pricing led to a spike in the cost per transaction when activity increased. Even with side-chains, layer 2 networks, or private networks, the cost to reach consensus between players in a game may be prohibitive, both in real currency and in precious computational resources that many games require.

End-user friction. Building a game that relies on cryptography means that cryptographic keys must be managed in a secure way. The current model for Web 3.0 games is to either pass the burden of key management on to the end-user/player or to abstract it in a way that removes the self-sovereign promise of the technology.

The perceived problems include:

A culture of speculation. Many game developers will not entertain the thought of incorporating Web 3.0 technologies because of the speculative nature of cryptocurrency markets. Too many Web 3.0 gaming projects used blockchain technology to raise money from vulnerable and non-accredited investors with the promise of high returns. As the market fluctuated, many investors lost their funds and were harmed. With the news surrounding the legal challenges of projects like Binance and FTX, game developers may choose to keep their distance from the entire Web 3.0 space.

Complexity. Integrating Web 3.0 technology may not be any more difficult than building a game, but the perceived complexity of managing cryptographic keys, integrating with blockchain nodes, or asynchronously coordinating blockchain and game messages can be overwhelming or unfamiliar.

Fun. Gamers want to play games. In most cases, gamers do not want to be bothered with the additional requirements of Web 3.0, including cryptographic key management through wallets, NFT marketplaces outside of the game, or even speculative value of their in-game items. If the added features of Web 3.0 introduce any friction to having fun, players may not play the game.

1.4 Tashi’s Discovery

In November of 2022, the engineering team at Tashi completed a proof of concept implementation of the Tashi Consensus Engine (TCE). The proof of concept was a multiplayer horse racing game where each player of the game was on a separate computer connected on a local area network (LAN), loading a simple horse racing game, and pressing the spacebar repeatedly. The player who pressed the spacebar 100 times first was the winner. In this demonstration, the objective was to use a consensus engine to capture user inputs, fairly order them, and reflect the results of user inputs to all players in the multiplayer session. The result was a multiplayer game where all players viewed the same results across multiple instances of the game without using an authoritative server. The success of this demonstration kickstarter an effort to find a product-market fit for TCE.

The Tashi business development team evaluated multiple industries for fit, including synchronized databases, high-frequency trading, gambling, decentralized message queues, and even a decentralized social network. The industry that showed the most promise and was immediately responsive was the gaming industry.

TCE could be used as a serverless leaderless peer-to-peer multiplayer gaming engine, now simply called “mesh multiplayer”. The Tashi core engineering team continued to develop, improve, and test TCE. An additional team was organized to lead the development of a software development kit (SDK) for Unity, the most popular game development engine. The objective of the SDK was to simplify the integration of mesh multiplayer mode for any multiplayer game developer to incorporate. To confirm the functionality of this SDK, the SDK team integrated mesh multiplayer into Unity’s dungeon crawler multiplayer game demo, which highlighted the feasibility of using TCE to keep high-end role-playing game clients in sync during game play.

In August of 2023, Tashi came out of stealth to present mesh multiplayer and the Unity demo at both Unity Developer Day in Copenhagen, Denmark and at DevCom in Cologne, Germany. The feedback from the game developer community was overwhelmingly positive and the Tashi team was invited to present again in San Francisco in December of 2023. The presentation in San Francisco was focused on Unity’s Entity Component System (ECS) framework. The SDK team built another demonstration of a multi-colony ant simulation highlighting TCE’s value in de-conflicting in-game events. Again, the feedback was overwhelmingly positive.

It has become clear that Tashi is building a reputation as the leader in applying Web 3.0 technology to the game development space in a way that brings value to Web 2.0 and Web 3.0 developers alike, demonstrating a real viability for the technology.

Tashi may help to resolve many of the problems of Web 3.0 adoption in the gaming space, notably:

TCE reduces the cost of real-time consensus for peer-to-peer gaming.

TCE’s latency is low enough to support live game sessions.

TCE’s throughput is high enough to support game event broadcasting.

The complexity of incorporating TCE is abstracted away through SDKs.

Tashi does not require developer or player participation in public network tokenomics.

TCE inoculates against lag griefing and local state manipulation cheats.

Tashi will enable privacy preserving regulatory compliance when integrated with in-game ad networks.

Tashi offers a mechanism for connecting game sessions with public networks, bridging the gap between current Web 2.0 and Web 3.0 ecosystems.

2 RESULTS

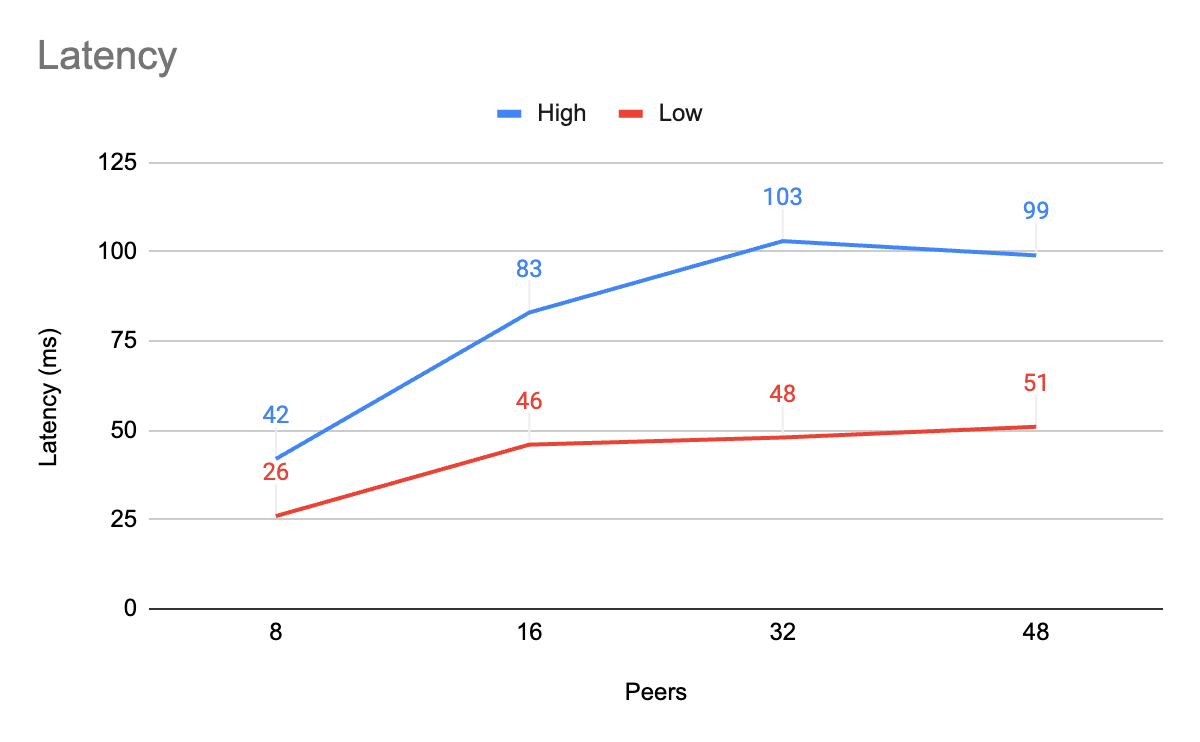

Two metrics are considered when measuring TCE’s performance: latency & throughput. Latency measures the time it takes to calculate the final order of a message after it has been submitted. This latency is sometimes referred to as “time to consensus” or “creation-to-consensus (C2C)”. Throughput measures the number of messages per second that reach finality.

We tested for latency using the following configuration:

Azure Standard D8ds_v5: 8 vCPU, 32 GiB memory, 300 GB SSD storage, 12,500 Mbps max network bandwidth

Sync interval: 8ms - 12ms

Transaction size: 128 bytes

The results showed latency as low as 26ms with 8 peers and as high as 103ms with 32 peers. Not shown on the graph is that the average throughput with this configuration was between 262,000 - 289,000 TPS for all peer counts. More peers slightly increases the throughput, but where most games only require between 60-120 TPS x the number of peers, TCE provides almost an order of magnitude of headroom for TPS.

This latency has proven to be sufficient for most multiplayer game types. Certain game types are more sensitive to latency than others. These game types include competitive first-person shooters (FPS) and some real-time strategy games where latency over 50ms is considered unacceptable. Additional tuning may bring TCE’s latency down even more and game netcode may be able to compensate for this latency. Importantly, most game types can be satisfied by TCE’s latency results with little netcode compensation.

Additionally we tuned for throughput which resulted in higher latency but also significantly higher throughput. With the same configuration as the latency test, but with emphasis on throughput, TCE is able to achieve 1,026,000 TPS with an average latency of 857ms, a low of 735ms, and a high of 977ms.

This is a significant milestone for public ledger applications. Not only can TCE be tuned for low-latency applications like gaming with throughput that is significantly higher than other DLT protocols, TCE can be tuned for high throughput applications with 2-3 orders of magnitude more TPS than most mainstream public layer 1 and layer 2 networks.

3 CONSENSUS

A distributed consensus algorithm aims to reach agreement between peers in a network with regard to application state. There are various mechanisms to ensure consistency between peers. The most fundamental mechanism to accomplish this is for the peers to agree on the order in which messages should be processed and potentially applied to the application state. As messages are generated by peers and distributed across the network, all peers should arrive at the same consensus order. If the algorithm guarantees consistent ordering for all honest and non-malfunctioning peers, the network becomes a type of decentralized message queue. Messages are ordered via the consensus protocol prior to being processed by each peer. This processing will encapsulate validation logic to determine if the messages should or shouldn’t be applied to the state. This validation logic should be agreed-upon prior to submitting messages into the network and should be identical between peers to ensure a consistent shared state. Additionally, states can be compared after mutation to ensure consistency between peers. This section will primarily focus on the initial mechanism of calculating consensus order.

Tashi Consensus is a directed acyclic graph (DAG) where each network-participating peer maintains a local version of a graph of information, where each node in the graph is cryptographically signed by its creator so it cannot be tampered with. This is the core concept of Tashi Consensus; much like hashgraph, peers distribute information through messages called Events, form a DAG, then calculate consensus independently. The algorithm guarantees that each peer will eventually and independently generate a consistent view of the graph [8]. This property is at the core of byzantine fault tolerance (BFT), which is the resilience of a fault-tolerant computer system to any fault presenting different symptoms to different peers [9]. In the case of a Tashi network, consensus can tolerate up to ⅓ of peers failing to report messages or reporting incorrect messages. In addition, Tashi consensus achieves BFT asynchronously, meaning that each peer calculates the consensus state independently of each other. There are no leaders or need to rebroadcast the results of such calculations to achieve consensus, only to gossip and apply the algorithm locally. This property is known as asynchronous byzantine fault tolerance (ABFT) and is unique to hashgraph-like algorithms.

Tashi Consensus results in fast, efficient, fair, and final ordering of messages submitted to the system. Tashi achieves fast consensus in two facets: latency and throughput. It can be tuned for low-latency scenarios achieving message finality in as little as 30 milliseconds or it can be tuned for high-throughput and achieve as much as 1,000,000 transactions per second. Tuning is key here. Multiplayer gaming does not concern itself with “transactions”, only packets of inputs from peer client games, and requires low latency. Public networks may be less sensitive to low latency and prioritize high-throughput and measure in terms of “transactions”. Both ends of the spectrum and all configurations in between are satisfied by the performance of Tashi Consensus. It is also efficient with regard to network bandwidth requirements and computational burden. With gaming as the forcing function for Tashi, speed and efficiency are critical to adoption by game developers where resources are already strained to maximize gamer experience. Finality is a property often ignored in public blockchain consensus protocols. This is a mistake. Finality is probably the most important property of a consensus algorithm, in that, without finality there is no guarantee of consistency between peers. In the “longest chain” model of traditional blockchain models, there is only a probability of consistency that is less than 1, meaning that it becomes less likely that the state of a system will change as blocks are added to the blockchain, but there is never an absolute guarantee that the state won’t change, if, for example, a longer chain emerges over time. With hashgraph-like algorithms, the probability of consistency is 1, meaning that there is a state that can be quickly calculated as final and that state is guaranteed not to change.

Fairness takes three forms. The definition for fairness is similar to hashgraph’s definition [7] but differs slightly, specifically with regard to fair timestamps:

fair access: meaning all peers are equally able to submit messages into the network without the risk of any one peer preventing the propagation of the submitted message. Even if malicious peers attempt to hinder a specific message, the gossip protocol is configured in a way to circumvent the blockage.

fair order: meaning that the order of a message in the final sequence is mathematically determined by an unbiased distribution of messages into the network. Message ordering is not controlled by, nor can it be significantly affected by, any one peer’s effort. If all messages are ordered as a result of being witnessed by 2/3 of the network peers, then any subset of peers less than 1/3 have no effect on the outcome of ordering.

fair timestamp: meaning that in the ordering process, the implementation may calculate a median timestamp for each message submitted into the network. This timestamp may be the median timestamp of when 2/3 peers in the network become aware of the message in question, or it may be a deterministically derived timestamp applied to the order of messages. Either way, any timestamp that is generated by consensus will be consistent between peers and be equally fair as with ordering.

The algorithm is broken down into two primary components: gossip about gossip, and virtual voting.

3.1 Gossip About Gossip

The gossip protocol for Tashi can be described as a "gossip about gossip" protocol. This term was originally included in the hashgraph white paper [7] and refers to the concept of not only sharing a peer’s events, but also sharing the events a peer has received from others along with hashes pointing to “parent events”. In essence, peers gossip not only the information they become aware of, but also how they became aware of that information.

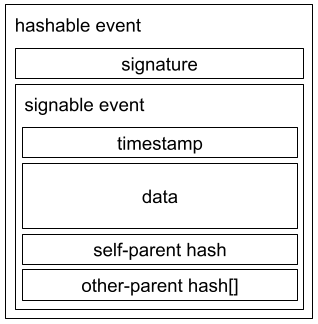

An event contains data, a timestamp, the hash of the last event created by the peer, known as the “self-parent”, and an array of hashes of the latest events received by other peers. This set of data is known as the “signable event” and is what is signed by the creating peer. Including the signature, the set of data is known as the “hashable event” which is used for reference by future events. Note that Tashi consensus differs from hashgraph in that hashgraph only references a single other-parent, while Tashi allows for multiple other-parents.

The result of this gossip about gossip model is a DAG that is built over time by each peer. The DAG is initially not consistent between peers, but by applying a virtual voting algorithm.

3.2 Virtual Voting

The most direct method of reaching consensus without a leader in a distributed system is to take a simple vote. All peers receive data then send votes about how the state should be updated to all other peers. This type of vote might require O(n2) voting messages, meaning that all peers send their votes to each other. If receipts of votes are required or multiple rounds of voting are required, more messages will be required. This method of voting is network-inefficient.

Tashi Consensus does not have a leader and does not pass around votes. It simply gossips events which contain references to previous events, generating a DAG. A virtual voting algorithm [7] can now be applied to this DAG. This virtual voting algorithm is made up of three functions:

Divide Rounds. This function assigns each event to a round. The first event generated by each peer is assigned to round 0. The first event in each round for each peer is that peer’s “witness event” for that round. Event A sees event B if B is an ancestor of A and A's ancestry does not contain a fork from the creator of B. Each new event inherits the maximum of the round numbers of its parents, and then its round number is incremented if it can strongly see more than ⅔ of that round’s witnesses. Event A strongly sees event B if there is a set of events C, where each event in C is an ancestor of event A which sees event B, and C is a supermajor set (it contains events from more than ⅔ of peers).

Decide Fame. This function finds witnesses that are famous. The goal of virtual voting is to arrive at a consistent set of famous witnesses for each round. For each witness in a given round, witnesses in later rounds “cast votes” on behalf of the peer who created them on whether or not that witness is famous. “Cast votes” is in quotes here because, as alluded to earlier, votes are not actually sent over the network. Instead, how a given witness votes is decided by a deterministic function whose sole input is the ancestry of that voting witness. Because all participants in the network agree on each event’s ancestry, each participant can run this function locally and be certain that they will see the same votes from each voting witness. Votes cast in one round are tallied by witnesses in the next round. Each tallying witness tallies votes only from witnesses in the previous round that they strongly see. The fame of a candidate witness is decided when any witness tallies supermajority agreement (more than ⅔) among peers that the candidate is famous, or is not famous. Not all witnesses will be famous. After a certain point, a peer can be sure that they have found all of the famous witnesses, and that if any more witnesses in the round exist that have not yet been transmitted to them, those witnesses will never be famous.

Find Order. Once fame has been decided, order can be determined. Any event that is an ancestor of any famous witness of a given round, and which was not finalized in a previous round, will be finalized in that round. The events finalized in a round are deterministically ordered depending on the DAG. The median timestamp among famous witnesses is taken to be the finalized timestamp of the round. Timestamps smeared across the time range between the previous round’s finalized timestamp and this round’s finalized timestamp are assigned to the finalized events in the round in ascending order to give each finalized event in the finalized order a unique and ascending finalized timestamp.

The result of this virtual voting process is a deterministic sequence of events, independently calculated by each peer as they asynchronously build their DAGs. The guarantee of the algorithm is that all peers will calculate the same final sequence of events.

4 PROTOCOL

4.1 Network Traversal

A major consideration in establishing a consensus network is how each peer will communicate with each other. TCE is expected to be used in many small and short-lived sessions, so the network traversal must be simple and reliable.

A multi-step approach is taken to establish these peer-to-peer connections:

All peers connect to a coordinating service to exchange public keys and network information. This may be a centralized service like Unity Lobby Service or a decentralized service like Hedera’s consensus service (HCS) or a blockchain’s smart contract. This information is used to generate an address book for the session.

Peers attempt to connect to each other directly using the address book information.

If peers cannot connect directly, a NAT traversal service may be used to facilitate NAT hole-punching.

If NAT hole-punching is unsuccessful, then the fallback method is to use a relay service.

While using a relay service is not ideal because it violates the “fair access” property of TCE, it may be necessary for various use cases including peer-to-peer gaming. Messages can still be secured against tampering because of the cryptographic signatures involved, but message delivery may be delayed or omitted with a relay.

4.2 Decentralized Message Queue

The result of establishing a TCE session between peers is a decentralized message queue in which all peers may broadcast messages as rapidly as necessary and TCE guarantees a tamper-proof and fairly ordered message stream. This message stream is consistent between all peers. This removes the need for message queue services. To the extent that the logic into which the stream of messages applied is identical between peers and is deterministic in nature, the resulting state of the systems will be consistent.

This mechanism may be applied to various use cases where order is critical, such as determining first-in first-out fulfillment services, high-frequency trading, synchronization of databases, decentralized layer-2 sequencing, and, in game development, deconfliction of game events.

4.3 Deterministic Lockstep

Deterministic Lockstep is a pattern of multiplayer game development where, instead of sending state updates to all players, all players simply send each other their inputs and each client calculates the result of those inputs [10]. This model requires some kind of message delivery mechanism, for which is what TCE is ideal. In order for players to stay in sync with each other, the game client must guarantee that, with the same inputs, each client will produce the same outcomes.

In this pattern all players’ game clients act as peers in a TCE session. Each peer captures local game inputs and gossips them to the other peers. All peers do the same. TCE orders all of these inputs fairly. Each peer locally calculates the order and applies the resulting message sequence to their game simulator to update the state of the game. If all players are running the same game version with the same simulation logic, they are guaranteed to remain in sync while applying the player inputs from TCE.

Additionally, game developers may wish to apply prediction and rollback to ensure a smoother game experience for players while still ensuring a consistent state.

4.4 Deterministic Randomness

Frequently distributed systems require some form of randomness. TCE provides an avenue for each peer to calculate pseudo-random values independently but to achieve the same random values between all peers. Because TCE uses cryptographic hashes and unpredictable but consistent ordering of messages, applications may use those properties to calculate deterministic pseudo-random values for use in applications. For example, this could be useful for random spawns, particle effects, and environment generation seeds in game.

Outside of gaming, this feature could be useful for smart contract coin flips, drawings, gambling, validator selection, and a host of other use cases in Web 2.0 and 3.0.

4.5 Unity DOTS/ECS

The first applications of TCE in gaming were in the development of the Tashi Network Transport (TNT), Tashi’s SDK for use in Unity’s game editor. TNT was bundled as a simple Unity package that could be used as a drop-in replacement for Unity’s network transport when developing multiplayer games.

Unity is developing a framework to help developers create more efficient game clients. Its data-oriented technology stack (DOTS) includes an optional development pattern called Entity-Component-System (ECS) which helps developers manage large numbers of objects in-game with minimal overhead. ECS separates in-game entities from the components that make up the entities and the systems that govern the logic of entities. The systems layer groups all of the logic of a game in a convenient location where ensuring determinism in game processes is more convenient than in previous frameworks.

ECS systems submit client inputs to TCE. Then clients receive the ordered stream of inputs. Each client pipes that stream of multiplayer inputs to an ingest system which then updates all other systems and ultimately the state of the game. Provided that all systems are coded deterministically on the ingest side, all games will remain in sync.

An added benefit of using TCE in Unity’s ECS is the benefit of trivially resolving event sequence conflicts. For example, in the Tashi Ant Simulation, when two ants arrive at a food token at approximately the same time, Tashi ensures that only one ant actually picks up the food token. This result is consistent across all player instances.

5 PLATFORM

While TCE provides a clear value for direct peer-to-peer multiplayer game sessions, the total opportunity is greater still. As previously observed, current Web 3.0 platforms struggle to appeal to traditional Web 2.0 game development studios due to low throughput, high latency, and cost prohibitive services. Even with the addition of Layer 2 solutions, Web 2.0 games require more organic value. TNT, as a game development SDK provides such value to multiplayer game developers, but supporting high throughput, low latency, and cost efficient multiplayer game sessions is just the forcing function for other valuable services and features, both inside and outside of the gaming industry. Tashi’s mission is to use best in class Web 3.0 technologies and package them as valuable and viable solutions for Web 2.0 industries; the gaming industry being the initial focus.

Game developers need multiple microservices to make their games work, including accounts, authorization, character management, inventory management, achievements, leaderboards, match-making, multiplayer servers, and a host of other services. TNT satisfies many of the multiplayer server requirements, but the opportunities are much broader.

Tashi has partnered with multiple Web 3.0 projects to build their solutions into a suite of back-end services. These partners include:

Aethir. Tashi will offer remote play, play testing virtualization, and end-to-end game testing using Aethir’s decentralized GPU orchestration platform.

Golem Network. Tashi is exploring offering continuous integration / continuous deployment testing pipelines using Golem’s decentralized CPU orchestration platform.

Ankr / Fluent. Tashi will offer Web 3.0 asset loading into and settlement from TNT game sessions, allowing players to bring their own inventories into their games, exchange assets in-game, and settle to the public network of their choice.

NES.TECH. Tashi will enable wallet management, advertising compliance, and token marketplaces using NES.TECH products.

REFERENCES

[1] O'Reilly, T. (2005). What Is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software. Retrieved October 12, 2023 from https://www.oreilly.com/pub/a/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html

[2] Web 2.0 - the web as a platform. Nov 04, 2021. (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2023 from https://www.minima.global/post/web-2-0-the-web-as-a-platform

[3] Edelman, Gilad. "What Is Web3, Anyway?". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on February 10, 2022. Retrieved October 12, 2023 from https://www.wired.com/story/web3-gavin-wood-interview

[4] Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf

[5] Vitalik Buterin et al. (2014). A next-generation smart contract and decentralized application platform. white paper (2014). Retrieved October 12, 2023 from https://ethereum.org/en/whitepaper

[6] Ethereum proof-of-stake consensus specifications. Ethereum Proof-of-Stake Consensus Specifications - Ethereum Consensus Specs. (n.d.). https://ethereum.github.io/consensus-specs

[7] Baird, Leemon C. III (2016) The Swirlds hashgraph consensus algorithm: fair, fast, Byzantine fault tolerance, Technical Report, Swirlds, Inc., SWIRLDS-TR-2016-01.

[8] Karl Crary. Verifying the Hashgraph Consensus Algorithm. 2021.

[9] Driscoll, K.; Hall, B.; Paulitsch, M.; Zumsteg, P.; Sivencrona, H. (2004). "The Real Byzantine Generals". The 23rd Digital Avionics Systems Conference (IEEE Cat. No.04CH37576). pp. 6.D.4–61–11.

[10] Gao (Meseta), Y. (2019, September 22). Netcode Concepts Part 3: Lockstep and Rollback. Medium. https://meseta.medium.com/netcode-concepts-part-3-lockstep-and-rollback-f70e9297271

[11] A Brief History of Web3 Gaming: What We’ve Learned So Far. (n.d.). www.blockchaincapital.com. Retrieved December 23, 2023, from https://www.blockchaincapital.com/blog/a-brief-history-of-web3-gaming-what-weve-learned-so-far